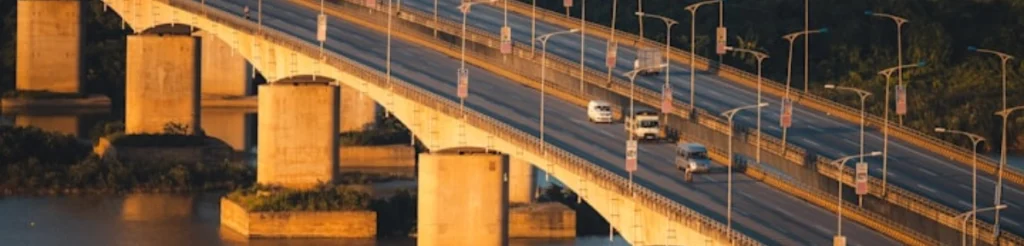

In global politics, infrastructure is rarely just about concrete, steel, and engineering. Bridges, pipelines, ports, and railways often symbolize power, influence, and economic control. When a major infrastructure project is completed, especially near a shared border, it can quickly become a political flashpoint. That’s exactly what is unfolding in the debate summarized by the phrase: “Canada built a bridge. Now Trump wants half.”

While the statement may sound dramatic, it reflects a broader discussion about cross-border infrastructure, trade leverage, and economic nationalism between the United States and Canada.

The Importance of Cross-Border Bridges

The United States and Canada share the longest undefended border in the world. Every single day, billions of dollars in goods and services move between the two countries. Trucks carry automotive parts, agricultural products, steel, technology equipment, and consumer goods back and forth across multiple crossings.

Bridges play a critical role in this relationship. They are not just transportation routes — they are economic lifelines. Cities like Detroit and Windsor are deeply interconnected, with supply chains that rely on seamless movement across the border.

When Canada invests heavily in new infrastructure that strengthens this trade corridor, it is not simply building a bridge. It is reinforcing economic independence, improving logistics efficiency, and reducing reliance on older infrastructure that may be privately owned or politically sensitive.

The Strategic Context

The discussion about ownership or revenue-sharing of a cross-border bridge ties into a larger political philosophy that gained prominence during Donald Trump’s presidency: economic nationalism.

Trump’s “America First” agenda emphasized:

- Renegotiating trade agreements

- Reducing perceived trade imbalances

- Increasing U.S. control over strategic assets

- Ensuring American taxpayers benefit from international deals

When large infrastructure projects connect the U.S. to another country, questions naturally arise about funding, ownership, toll revenue, and long-term control.

If Canada funds and builds a bridge that directly benefits U.S. commerce, should the United States have a stake? Should there be shared ownership? Should revenue be divided? These are not simple engineering questions — they are political and economic ones.

Trade Tensions and Leverage

During Trump’s presidency, U.S.-Canada relations went through both cooperation and tension. The renegotiation of NAFTA into the USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) was a prime example.

Trump frequently argued that previous trade deals disadvantaged American workers. His administration imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum, including imports from Canada, citing national security concerns. Canada responded with retaliatory tariffs.

In that climate, even infrastructure projects could become bargaining chips.

A bridge that improves trade flow might be seen as beneficial to both countries. But in a negotiation mindset, one side might argue that improved logistics primarily serve foreign exporters. If Canada finances a bridge that enhances its export capacity into the U.S., political voices in Washington might argue that American participation — or profit-sharing — is justified.

Infrastructure as Power

Throughout history, infrastructure has been linked to power. Ports determine trade routes. Railroads shape industrial growth. Highways transform regional economies.

In the 21st century, control over infrastructure can influence:

- Customs enforcement

- Toll revenue

- Border security

- Trade efficiency

- Political leverage

When a country builds and controls a major crossing point, it holds a strategic asset.

If Trump or his allies argue that the United States deserves “half,” the claim may not literally mean cutting the bridge in two. Instead, it could refer to:

- Shared governance

- Revenue sharing

- Cost sharing

- Political oversight

- Security authority

The symbolism, however, is powerful. It reflects a broader philosophy of asserting American influence over international partnerships.

Canada’s Perspective

From Canada’s standpoint, building a major infrastructure project independently demonstrates strength and self-sufficiency. It reduces reliance on private or foreign-controlled assets and ensures long-term control over a critical economic corridor.

Canada has historically valued stability in its trade relationship with the U.S., but it has also worked to diversify trade partners globally. Investments in infrastructure are part of ensuring smooth export operations regardless of political shifts in Washington.

If the U.S. demands ownership or revenue-sharing after Canada has funded and constructed a bridge, Canadian officials might argue:

- The investment risk was theirs

- The financing was theirs

- The planning and development were theirs

- Therefore, control should remain theirs

Such disputes can quickly escalate into diplomatic friction.

Economic Nationalism vs. Economic Integration

The situation highlights a larger global tension between two models:

1. Economic Integration

Countries cooperate, share infrastructure, and benefit mutually from trade flows.

2. Economic Nationalism

Countries prioritize domestic advantage, renegotiate terms aggressively, and seek stronger control over cross-border assets.

Trump’s political brand strongly favored the second approach. His rhetoric often framed international deals as zero-sum — one side wins, the other loses.

However, many economists argue that U.S.-Canada trade is deeply integrated and mutually beneficial. Automotive manufacturing, for example, relies on parts crossing the border multiple times during assembly. Disruptions or ownership disputes could increase costs for both sides.

The Political Optics

Infrastructure disputes also have domestic political implications.

In the United States, a leader demanding a stake in a foreign-funded project could frame it as protecting American taxpayers and workers. Supporters might view it as strong negotiation.

In Canada, leaders defending full ownership could frame it as protecting sovereignty and resisting political pressure from a larger neighbor.

The issue becomes not just economic, but symbolic of national pride and independence.

What It Means for the Future

If political leaders begin treating cross-border infrastructure as contested territory rather than shared opportunity, future projects could become more complicated.

Potential consequences include:

- Slower approval processes

- Increased political scrutiny

- More detailed bilateral agreements

- Higher financing costs

- Reduced investor confidence

On the other hand, the controversy could also push both nations to clarify rules for future projects — specifying funding obligations, ownership rights, and operational control in advance.

The Bigger Global Picture

This debate also fits into a broader global trend. Around the world, infrastructure is increasingly tied to geopolitical competition.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative invests heavily in foreign infrastructure projects, sometimes leading to disputes about ownership and influence. In Europe, energy pipelines have become political flashpoints.

North America is not immune to these dynamics. Even between close allies like Canada and the United States, strategic assets can trigger complex negotiations.

Conclusion

“Canada built a bridge. Now Trump wants half” captures more than a simple dispute over steel and toll booths. It reflects the evolving nature of economic nationalism, strategic infrastructure, and cross-border politics.

Bridges are meant to connect. But in a world shaped by shifting political ideologies and trade priorities, even a bridge can become a symbol of leverage, control, and negotiation power.

Ultimately, the future of U.S.-Canada infrastructure cooperation will depend on whether leaders view shared assets as mutual gains or contested advantages. The answer will shape not just one bridge — but the broader economic relationship between two of the world’s closest trading partners.